What set the human lineage on a separate path from chimpanzees sometime between ten million and six million years ago? The first scientists to study the origins of our species speculated that brain enlargement led the way in driving human evolution. However, nearly a century’s worth of fossil discoveries in Africa instead point to the ability to walk on two legs (bipedalism), and perhaps a slightly lower-quality diet compared with that of chimpanzees, as the first distinguishing features of the earliest hominins (species more closely related to humans than to chimpanzees)1. Even so, much about the first hominins and why they evolved remains mysterious. Was the last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees similar to a chimpanzee, a gibbon, a monkey or something completely different? And did bipedalism evolve before, during or after the split between humans and chimpanzees? Writing in Nature, Daver et al.2 present fossil evidence that helps to address some of these questions.

There are almost no fossils unambiguously recognizable as being the immediate ancestors of chimpanzees or the other living African great apes. The best available evidence to address some of the key open questions has instead come from the oldest known hominin species (Fig. 1). These include Ardipithecus ramidus, dated to 4.3 million to 4.5 million years ago; Ardipithecus kadabba, dated to 5.2 million to 5.8 million years ago; Orrorin tugenensis, dated to about 6 million years ago; and, last but not least, Sahelanthropus tchadensis, dated to about 7 million years ago. Sahelanthropus was previously known from only a partial cranium, a few jaw fragments and some teeth3. Daver and colleagues describe three more fossils attributed to Sahelanthropus: a partial leg bone (femur) and two arm bones (ulnae), the characteristics of which suggest that this species not only walked on two feet but also climbed trees.

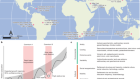

Figure 1 | The evolution of bipedalism. Hominins (species more closely related to humans than to chimpanzees) evolved from an ancestor shared with African great apes (such as chimpanzees and gorillas), which move by walking on four legs and climbing trees. Sahelanthropus tchadensis is the oldest known hominin species. It has features that suggest it was an occasional bipedal walker, including leg-bone characteristics (too subtle to see on the scale of this femur image) that Daver et al.2 report. The authors indicate that arm bones (not shown) of this species were adapted for tree climbing. A similar mix of adaptations for occasional bipedal walking and tree climbing characterizes early hominins of the genus Orrorin and Ardipithecus. Species of the genus Australopithecus were comparatively more effective habitual bipedal walkers, but retained adaptations for climbing trees. Species in the genus Homo have numerous adaptations for effective bipedal walking and for running, but have lost most adaptations for tree-climbing. Femur images are not shown at their relative scale (images, apart from that of Australopithecus afarensis, are from ref. 2; A. afarensis image: Daniel E. Lieberman). Note that the Sahelanthropus femur is missing joints at the end of the bone, which would have provided insights into how this species moved.

Sahelanthropus was discovered in Chad in 2001, and immediately caused considerable excitement. It was not only about one million years older than any other known hominin species, but was also found 2,500 kilometres away from the closest known hominin fossils in eastern Africa. The cranium of the specimen, nicknamed Toumaï (meaning ‘hope of life’ in the local Daza language), had a chimpanzee-like brain volume of between approximately 360 and 390 cubic centimetres. Compared with chimpanzees, Sahelanthropus has slightly larger molar teeth with thicker enamel, smaller upper canine teeth that don’t sharpen themselves against the lower premolar teeth and a slightly flatter face4 — characteristics that are similar to those of later hominin species.

Read the paper: Postcranial evidence of late Miocene hominin bipedalism in Chad

Perhaps the most exciting feature that Toumaï shares with other hominins is the anatomy of the skull opening (foramen magnum) at the base of the skull where the spine connects and the spinal cord emerges. The foramen magnum of four-legged animals is typically located towards the back of the skull and is oriented backwards, whereas in Sahelanthropus it is positioned near the middle of the skull and is oriented downwards5. Combined with the horizontal angle of the back of the skull where the neck muscles attach, a downwards-oriented foramen magnum provides strong evidence that, like bipeds, Sahelanthropus balanced its head on a vertical neck6.

The hominin status of Sahelanthropus is controversial. In addition to debates about the geological age of the fossil material, and reservations about the cranium’s reconstruction, researchers have speculated that Sahelanthropus’s similarities to hominins are just comparable characteristics that evolved independently7. This is an important critique, because independent similarities can and do evolve among closely related species, a phenomenon known as convergence. That bipedalism evolved more than once among apes is thought by many to be unlikely, but requires further testing. Hypotheses of bipedalism have previously been questioned8,9 for extinct species of ape, such as Oreopithecus and Danuvius.

Some scientists have reserved judgement on whether Sahelanthropus was a biped because of the absence of supporting evidence from parts of the body other than the skull, such as the pelvis, femur or feet. And to add to the controversy, such potentially relevant evidence was known to exist but was unavailable to researchers. When the Sahelanthropus cranial material was discovered in 2001, a femur and ulna were also retrieved, together with thousands of other fossils. It was not until three years later that the femur was recognized as probably belonging to a hominin by researchers unaffiliated with the team working on Sahelanthropus, and an account of the femur’s discovery was published10 in 2009. A subsequent analysis argued that the femur’s shape was more similar to that of apes than to that of known bipedal hominins, although this assessment was based on just a few measurements of the femur and on 2D photographs11.

Hominin footprints at Laetoli reveal a walk on the wild side

The ulna found in 2001 and another discovered in 2003 were subsequently recognized as being those of hominins. Given all of this uncertainty and controversy, Daver and colleagues’ analysis of the Sahelanthropus femur and ulnae is of considerable interest. But don’t expect a full resolution just yet, because the femur consists mostly of a shaft that doesn’t have the joints at either end (Fig. 1) that would provide most of the information needed to infer Sahelanthropus’s posture and how it walked.

Nevertheless, the authors have squeezed as much information as possible from the fossil data, focusing on features that they suggest are consistent with bipedalism. First, as is characteristic of bipedal hominins, the base of the femur’s neck seems to be oriented slightly towards the front of the body and is flattened. The upper part of the femur is also slightly flattened, and the sites at which the gluteal muscles insert are fairly robust and human-like. In addition, the cross-sectional shape of the femur at several locations falls within the range expected for hominins. This feature is indicative of a femur that shows resistance to the sideways-bending forces that are characteristic of those encountered by bipedal hominins.

The researchers also point to traces of a bony ridge called a calcar femorale, a region of dense bone thought to buttress the upper femur from the forces produced by walking upright. However, this feature is not necessarily diagnostic of bipedalism12.

Whatever you might think about the femur, the ulnae are unquestionably chimpanzee-like and are clearly well adapted to climbing trees. In addition to being short, the bones have highly curved shafts, indicating the presence of powerful forearm muscles that could flex the elbow during climbing. The elbow joints are also ape-like, with a shape that would be able to cope with high forces while flexed — a position typical for tree climbing that is mechanically challenging.

The Sahelanthropus femur doesn’t have ‘smoking-gun’ traces of bipedalism, but it looks more like that of a bipedal hominin than that of a quadrupedal ape. When considered in conjunction with the orientation of the foramen magnum, which is compatible only with bipedalism, it seems reasonable to infer that Sahelanthropus was some type of biped and that, like later hominins such as A. ramidus, it was also well adapted to climbing trees. A few million years after Sahelanthropus and Ardipithecus, another genus of hominin — Australopithecus — evolved to be highly effective walkers while retaining many adaptations necessary for climbing trees. It was in only the human genus, Homo, that hominins lost the adaptations needed for moving through the trees as they became runners. That said, we know little else about the gait of Sahelanthropus. A mixed repertoire of walking and climbing makes sense given that Sahelanthropus lived near a lake with woodland adjacent to it.

It bears repeating that, apart from bipedalism and slightly more hominin-like teeth and face, many Sahelanthropus features are similar to those of a chimpanzee. This resemblance makes sense if the last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees was chimpanzee-like1 and Sahelanthropus evolved very soon after humans and chimpanzees diverged. But these and other inferences are sure to remain the subject of much debate, especially until more fossils are found to fill the evolutionary record, not just of humans, but also of chimpanzees.

Read the paper: Postcranial evidence of late Miocene hominin bipedalism in Chad

Read the paper: Postcranial evidence of late Miocene hominin bipedalism in Chad

Hominin footprints at Laetoli reveal a walk on the wild side

Hominin footprints at Laetoli reveal a walk on the wild side

Those feet in ancient times

Those feet in ancient times